Translate But Don’t Editorialize

We just saw a case of an attempt to translate the pragmatics of a text instead of the text itself.

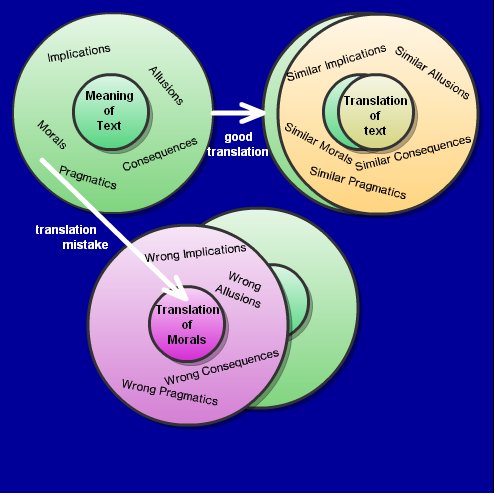

In general, a text will have a variety of implications, morals, allusions, etc. I think that a good translation of the text will match the original with a translation that has similar implications, morals, allusions, and so forth. Sometimes, however, translators are tempted to focus on one aspect of the text; then they translate that aspect instead of the text. The chart at the right depicts the two approaches.

In general, a text will have a variety of implications, morals, allusions, etc. I think that a good translation of the text will match the original with a translation that has similar implications, morals, allusions, and so forth. Sometimes, however, translators are tempted to focus on one aspect of the text; then they translate that aspect instead of the text. The chart at the right depicts the two approaches.

For example, the “golden rule” is explained in Matthew 7:12 as outos gar estin o nomos kai oi profitai, “for this is the law and the prophets.” Ignoring for the moment what exactly “the law and the prophets” is (probably the Jewish Canon at the time), we still find translation variations for outos gar estin. For example (with my emphasis):

- this is…. (ESV, NAB)

- this sums up…. (NIV)

- this is a summary of…. (NLT)

- this is the meaning of…. (NCV)

- this is what [the Law and the Prophets] are all about…. (CEV)

- add up [God’s Law and Prophets] and this is what you get. (The Message)

I think that the NIV, NLT, NCV, CEV, and The Message get it wrong. Each of those versions translated something related to the text instead of the text itself.

Presumably, the translators for some of these versions decided that it’s just not true that the Law “is” the Golden Rule, but if so, what they missed is that it’s equally (un)true in Greek as it is in translation.

Perhaps the point of the passage is that the golden rule sums up the Law and the Prophets, but again, even if that’s true, “sums up” doesn’t seem like the right translation, because I don’t think it’s the job of the translation to jump from the text to its point for us.

By focusing on the point, or the moral, or the message, of the text, translators disguise their interpretation as translation. (This is, by the way, what I think Dr. Leland Ryken dislikes so much about the translations he criticizes, and I think in this regard he is correct to protest.)

I no longer actively write this blog, but you can find me at Ancient Wisdom, Modern Lives

Subscribe Now I'd love to see you there!It seems to me that when the lines between commentary and translation are blurred, it does a disservice to both.

Bible Bible translation CEV ESV golden rule Matthew 7:12 NAB NCV NIV NLT the law and the prophets The Message translation

13 Responses

I think that this is a major problem when we look at Bible translations that are considered a “Thought-for-thought” translation. It is hard to produce a dynamic equivalent translation without at least some editorializing. The Theological preferences of the translator(s) is inevitably bound to come across even in the simplest and most straightforward of verses.

I agree with you assessment about the blurring of the translation and commentary being a disservice to both, and also to the reader. With so many good, formal equivalent translations giving an easy to understand “word-for-word” rendering, I would never advise anyone to rely on the others as their primary translation.

Interesting post and good points.

In Christ,

Loren

Loren, thanks for stopping by.

I’m not sure I agree. I think the false solution of “word for word” as an antidote to paraphrase is another disservice that has been done to Bible readers. I also think that frequently the “word-for-word” translations shine best when they abandon their alleged word-for-word philosophy.

For example, still with Matthew 7:12, the KJV rendition of the start of the line is all but incomprehensible to modern readers: “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them.”

The “essentially literal” ESV does a reasonable job fixing the translation here: “So whatever you wish that others would do to you, do also to them.” But the translators changed anthropoi into “others” (rather than going with “men” or “people”), didn’t translate the word outos (“thus”), even they do translate it in exacly the same phrase 10 chapters later in Matthew 17:12 (“So also….”). And so forth. The ESV’s success here lies in abandoning a word-for-word rendition.

There’s some question as to what exactly the original point was. The NRSV gives us “In everything, do to others as you would have them do to you.” If they’re right about “in everything” (as opposed to “do everything to others…”), then I think that that thought-for-thought translation is better than the ESV. And even if not, I think their approach is better here, because this strikes me as a sentence that cries out for a clear translation, not for a translation of its parts.

Is it possible that the point of this passage is to say…

“A gift, whether from God or men, is given to be useful to its recipient [Matt 7:9-11],

therefore,

All those things that you wish that other people would do for you, do THOSE things to other people,

because the law, and also the prophets, work as we saw in verses 9-11.”

In other words, OUN and hOUTOS seem to be referring to the principle of “act benevolently and appropriately as outlined in the 3 preceding verses.”

Perhaps leaning toward the “word-for-word” translations is an overly simplistic approach, but to me it seems to be a matter of which style is preferable. There are, of course, some translations that seek to produce a sort of hybrid between formal and dynamic equivalence, but it becomes apparent when examining these that they are not without editorializing, as well.

This is, in my view, the challenge faced when producing any type of translation, and that is: Which English term most accurately expresses what the writer is intending in the original language? This is not always as straightforward as it might seem. I find it remarkably frustrating that the Greeks endowed their language with such a great degree of specificity when it came to expressing certain ideas (consider the distinction between certain terms such as “phileo” and “agapeo” which denote differing nuances of “Love”), yet the ambiguity and interchangeability of the preposition “ek” has led to disputes over entire doctrines as well-intentioned interpreters seek to determine which English preposition most accurately conveys the intended meaning. Often times, this determination is made based on little other criteria than doctrinal preference and denominational background.

So what is the answer, particularly for the linguistically untrained layman whose desire is to hold in his hand a single, accurate volume which correctly communicates to him the Word of God? Which type of translation best relates the original intentions of the writer, or better yet, the Writer (being the Spirit of God), unfiltered by denominational schisms, disputable dogmas, or capricious human preference? In other words, as your post title states, which translation style is the LEAST susceptible to editorial revision?

Transliterations (such as Young’s or Darby’s) can be practical for those unfamiliar with the original languages, the text adhering more closely to the original, albeit at great sacrifice to the fluency of the narrative. But even then, the translator is forced to interject his own judgment into the translating by selecting how best to render each term into the vernacular. Even transliterations are not entirely without editorializing.

To sum up what I am saying, let me just state that I personally believe that the answer lies in the application of sound hermeneutics in correctly determining the original intentions of the text. Etymological evaluation can be informative, but it must never subjugate contextual.

Ultimately, it is the direct illumination by the Spirit of God which leads to “rightly dividing” the Word of God. Apart from this, we can never know the mind of the Lord (1 Cor. 2:16). Sound hermeneutics will insure that we do not stray from sound doctrine, nor that we enter into private, subjective interpretation; but if we are interested in correctly understanding what the Bible is saying, we must, above all else, stay in fellowship with the One Who wrote it.

Thanks, Joel, for this very thought-provoking post. God bless you.

In Christ,

Loren

“Then opened he their understanding, that they might understand the scriptures,” (Luke 24:45)

So what is the answer, particularly for the linguistically untrained layman whose desire is to hold in his hand a single, accurate volume which correctly communicates to him the Word of God?

Loren,

Thanks for your detailed reply.

About a month ago, I was asked to recommend a single Bible translation. (My short answer is the NRSV or the NAB; my more detailed answer is here.)

But I “agree with your question,” in that I think it’s very hard to find a single, accurate, quality translation of the Bible. This is a little surprising in light of the enormous effort invested in Bible translation, and more than a little unfortunate in light of the Bible’s centrality.

Wow. If I am honest, all of the quibbling over translation here makes me feel sick. “It’s very hard to find a single, accurate, quality translation of the Bible”??? You must be joking!

Meanwhile there are over a thousand languages in the world where work hasn’t even been started on a translation. Quit quibbling about English translations and go translate the Bible for some people overseas who don’t have a lick of the written Word of God.

Maybe then you will understand just how difficult translation really is.

With regards to the word-for-word thing, I’d like to put my two cents in. Yes, I realize that the word-for-wordness of God’s Word is important. I believe in verbal inspiration and believe that the Bible makes a compelling case for it’s own verbal inspiration (such as arguments hinging on the tense of a verb or the number of a noun). However, at the end of the day, you have to realize that language is more dynamic then math. Yes, language has structure, formula, etc. But it also deeply transcends structure and formula in that its whole essence is the communication of ideas/meaning.

Even a change in my facial expression as I say a particular sentence can communicate two completely different things with the same sentence. So while there is a place for word-for-wordness, it should not be at the expense of understanding the author’s intention. If that means that a figure of speech in Greek that is unintelligible when translated literally in English ends up being translated “pragmatically”; So be it! The important thing is that we understand God’s intention, the idea that he is trying to communicate to his people, the intention of the author.

Not everybody is a scholar. Translations like the NIV have these people in mind. Translations like the NASB don’t. When it comes right down to it we need and should use both the word-for-word and the thought-for-thought.

I’ve been blessed countless times reading through the NIV to find places where they have nailed the emphasis of the Greek. In fact, I didn’t even know those emphases were there because they simply didn’t come through in NASB’s often clumsy word-for-wordness. Other times I notice an emphasis in NIV and I’m suspicious and soon discover that it’s pretty unclear in Greek too and represents a best guess.

What’s more important having it word-for-word and not being able to understand it all, or having an idea suggested of what it might mean?

What about children? Do you expect them to be reading through commentaries and asking their parents countless questions that they can’t answer about why their “perfect” translation doesn’t make any sense?

As much as I’d love to have all the beauty, poetry, rhetoric, metaphor, etc come through in the English in tact; it’s just not going to happen. There are other people in the world who don’t have the gospel or any translation of the Bible for that matter. So why don’t we put all that we do know about Bible translation to better use?

Joshua,

Thank you for your detailed and honest comment.

You are not the first the raise the objection that we should “quit quibbling about English translations” when so many languages have no translation at all.

I have enormous respect and admiration for the people who devote years and sometimes decades to translating Scripture into a new language. (I still vividly remember presenting a paper at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven and then afterwards hearing about the gap between theory and practice. A couple living in Africa told me they usually had no electricity.)

Still, I think that three points are worth emphasizing.

First, frequently the errors in English translations are not as minor as some people make them out to be, so a lot of the work on English translation is not “quibbling” at all. Just to pick a recent example (read more here), I think it’s a big deal whether I Timothy 2:12 prohibits all women from teaching men or not.

Secondly, I think that the lack of translations in some parts of the world shouldn’t stop us from getting better translations here, for two reasons. They will help English speakers better understand what they are reading, and — because many new translations start with an English translation — they will ultimately help many other new translations as well.

Thirdly, there seems to be a belief among English readers that the English translations are accurate. (Just the fact that some people revere the KJV or the NKJV shows how deeply these sentiments run.) How accurate do people hearing, say, the Setswana audio Bible think their version is? I don’t know. But in my experience — for better or for worse — English speakers expect accuracy in translation.

So unless we’re willing to give up the goal of accuracy, I think we have to keep working toward better translations.

Good post, Joel. I wonder if there’s something theological influencing the translations of Mt 7:12. The exact same phrase, outos gar estin, is in Mt 3:3 – where most English Bible translators have pretty much what KJV does: “For this is.” Some will leave out the “for” and some will make the verb past tense.

(The Message, the NLT, and, interestingly, NAB are the odd balls on Mt 3:3 – respectively:

“John and his message were authorized by Isaiah’s prophecy”

“The prophet Isaiah was speaking about John when he said”

“It was of him that …”)

My musings on Matthew 7:12 were because I find the assertion that “the law and the prophets” and “do unto others as you would have them do unto you” are identical to be patently false. It is one thing to say that you died to the law to be married to Christ but another to say that the law really was never anything but complicated way of saying “do unto others.” It is a ridiculous assertion. Consider Paul, saying the same:

Ro 13:8 Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law.

Or:

Ga 5:14 For all the law is fulfilled in one word, even in this; Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

This is just absurd.

The law contains prohibitions against eating various kinds of food and doing certain activities on the seventh day of the week. It prescribes feasts and temple activities.

To say that any or all of that is lumped into one saying, “love your neighbor” is doing a great injustice to common sense.

And the prophets. They spoke of various calamities and what not. They declared God’s special love for Israel and Jerusalem. They pronounce a curse on those that violate the statutes of the law, or worship idols, or run to other nations for help.

So it is clear that saying that these are identical, if that is indeed the import of the words, is shmaltzy and sentimental rather than a sound hermeneutic. They are apples and oranges.

This was why I was thinking perhaps hOUTOS had something else in mind contextually. But the more I look, the more my ideas require hOUTWS, and there isn’t even a variant for that.

It appears that Matthew and Paul were force fitting the ideas of the Rabbis onto their text.

Moses love of neighbor.

Of course, we can say that “the law” is the law of Christ, rather than the law of Moses, but that is hardly apparent from the context.

I’m not sure that “is” implies identity, but I think the broader and more important point is that it’s not the job of the translation to resolve such issues. If the line is “patently false” in Greek — and I’m not saying it is false, but even if it’s false — then I think it should be in English, too. It seems to me that readers in English should be able to judge the content of the text without worrying that the translation has prejudiced the issue.

Looking at the issue another way, can you really call something a translation if it takes text that’s false and renders it as text that’s true?

I wonder if there’s something theological influencing the translations of Mt 7:12

I’m almost sure there is. I think some translators feel the way WoundedEgo does — that the text as it stands is “patently false.” But as I wrote to him, I don’t think it’s the job of translators to change the text to make it more to their liking. (As it happens, in this case I don’t think the original is so problematic, but that’s really beside the point.)

I am “okay with” letting a difficult text stand as it is, but first I try to make sure that I haven’t missed some other way of looking at it. Many apparent difficulties have been resolved that way before.

I’m still exploring alternatives to “identity,” but that seems to be the case, and Paul corroborates. In case anyone is fuzzy on “identity,” I’m reproducing a dictionary description as it makes it clear:

Main Entry: iden·ti·ty

Pronunciation: \ī-ˈden-tə-tē, ə-, -ˈde-nə-\

Function: noun

Inflected Form(s): plural iden·ti·ties

Etymology: Middle French identité, from Late Latin identitat-, identitas, probably from Latin identidem repeatedly, contraction of idem et idem, literally, same and same

Date: 1570

1 a : sameness of essential or generic character in different instances b : sameness in all that constitutes the objective reality of a thing : oneness

2 a : the distinguishing character or personality of an individual : individuality b : the relation established by psychological identification

3 : the condition of being the same with something described or asserted

4 : an equation that is satisfied for all values of the symbols

5 : identity element

http://m-w.com/dictionary/identity

“Similarity,” which is what would be more sensible to my thinking, would require hOUTWS, rather than hOUTOS, no?

And Paul’s writings seem to repeat the identity thing.

There is another relevant text. This one also makes more sense to me than identity, and that is the idea that the civil statutes of the law “hang” on the *moral* law like the serpent “hung” onto Paul’s hand. Separated from his hand, they fall harmlessly into the fire:

Mt 22:40 On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets.

Acts 28:

3 And when Paul had gathered a bundle of sticks, and laid them on the fire, there came a viper out of the heat, and fastened on his hand.

4 And when the barbarians saw the venomous beast hang on his hand, they said among themselves, No doubt this man is a murderer, whom, though he hath escaped the sea, yet vengeance suffereth not to live.

5 And he shook off the beast into the fire, and felt no harm.

That I get. But when one says that the commands of Torah and the urgings of the prophets were all just urging love of neighbor is like bad math, that hurts to look at. It is like the Trinitarian formula of “three equals one!”

Put yourself into the shoes of a Jew who is told by John Lennon that “all you need is love.” It doesn’t matter what you eat, because whatever you eat just goes out your behind the next day. “Nothing is unclean of itself” and “God made every creature as fair game for Wednesday night pot luck dinners.” It isn’t fair. Like Peter said, “No, lord, I’ve never eaten anything unclean!”

Like I said, okay, if the rules have changed… but to say that the rules were never what they seemed? That the new “all-you-can-eat buffet” is the *same* as “blessed be God who has separated the clean from the unclean” is simply confusing, if not goofy and unacceptable.

…perhaps the idea of Matthew 7:12 is simply that it is identity of part of what the Law and Prophets say. If I were to editorialize: “For this is what the Law and Prophets say on this matter.” Of course, I would prefer for my translation to be more more objectively rendered “for this is the Law and the Prophets.”