Accuracy versus Readability: another false choice in Bible translation

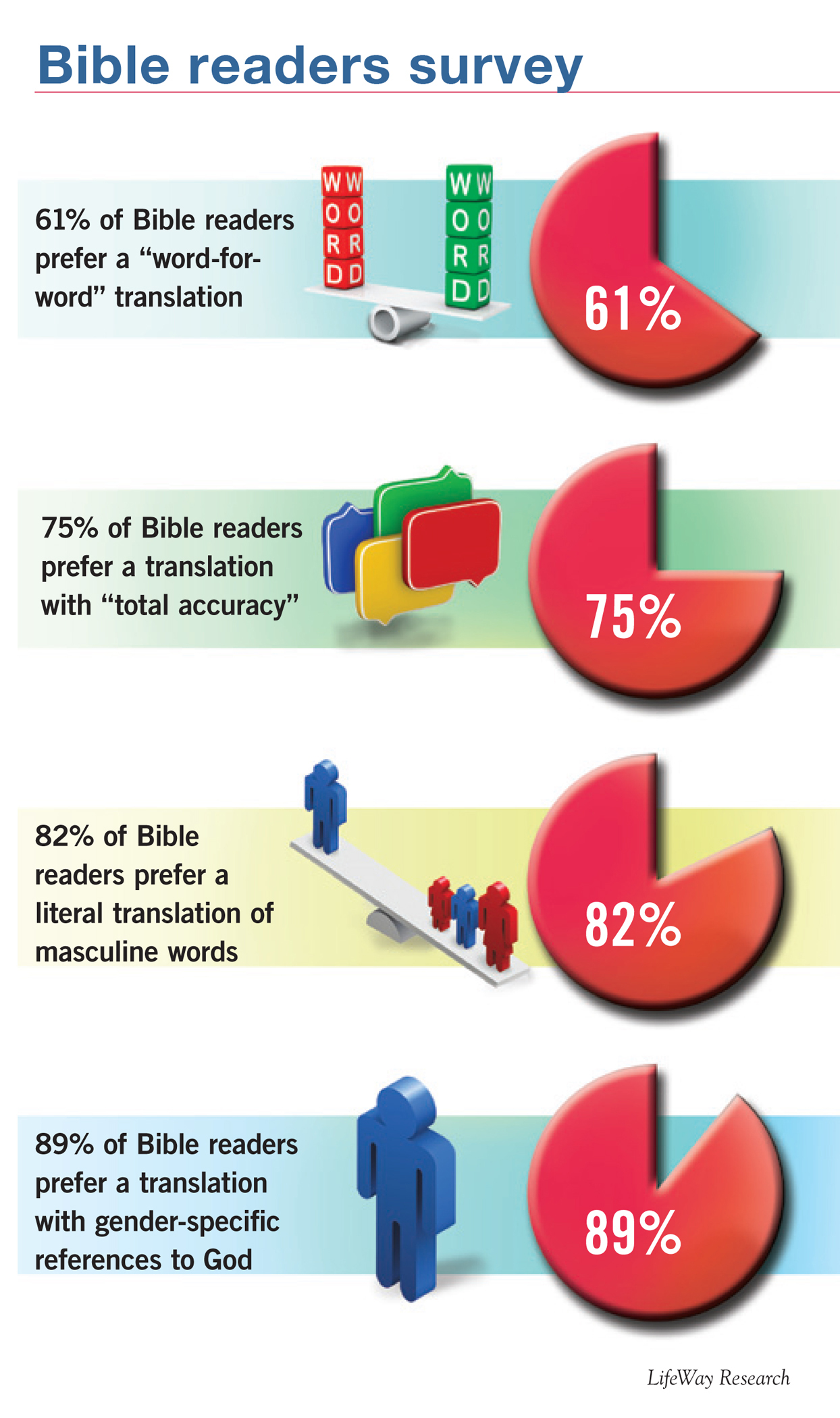

According to a recent report by Lifeway Research, described by David Roach in the Baptist Press, “most American Bible readers … value accuracy over readability,” which is why they “prefer word-for-word translations of the original Greek and Hebrew over thought-for-thought translations.”

There is overwhelming evidence and near universal agreement among linguists that word-for-word translations are less accurate than other approaches.* Equally, translators generally agree that, when the original is readable (as much of the Bible is), accuracy and readability go hand in hand. That is, valuing accuracy is often the same as valuing readability.So what’s going on?

One question might be, “why do so many Bible readers still make the basic mistake of choosing the wrong translation (word-for-word) to achieve their goal (accuracy)?”

Another question might be, “is there some merit to the word-for-word translations that linguistic approaches are missing?” (I try to answer that question here: “the value of a word for word translation.”)

A third question might be, “is there something about thought-for-thought translations that makes them unsuitable even though they ought to be more accurate?” (I think the answer is yes.)

I no longer actively write this blog, but you can find me at Ancient Wisdom, Modern Lives

Subscribe Now I'd love to see you there!But I’m starting to wonder about the ongoing Bible-translation debate that pits accuracy against readability, and words against thoughts. Maybe it’s not primarily about language and translation at all. Maybe the issue is part of the broader disagreement about the roles of religion of science and how to balance the two. In other words, sticking to a word-for-word translation may be like opting for a literal biblical account of history and rejecting evolution, at least for some people.

What do you think?

[Updates: Mike Sangrey has a follow-up on BBB with the delightful title, “Headline news: Accuracy Battles Readability — Surreality Wins.” And in a post on the same topic at BLT, J. K. Gayle creates what I think is the right frame of mind with, “Imagine having to chose between accuracy and readability in a translation of Orhan Pamuk or Homer or Virgil.”]

(*) Just for example, my post on “what goes wrong when we translate the words” gives a sense of one problem; my post on “what goes wrong when we translate the grammar” gives another. My recent TEDx video explores the issue in more detail, and my And God Said goes into much more detail.)

Bible Bible translation dynamic equivalence formal equivalence translation

17 Responses

There is no question that some who contributed to the ESV, for example, prefer it based on its claim to be a “essentially literal” word for word translation. The basic idea is to avoid doing “too much” interpretation, but they also claim that other translations “omit words” or “change words”. The more I study, the more I find that this is a false way of understanding the challenge, so I greatly appreciate your insights in this area.

I hold that it is important to grasp both, but in practical terms, what I like is to have someone explain in footnotes how the English rendering differs significantly from the underlying text in a footnote. IE: It is okay to translate “human one” but I want to know that the literal was “son of [a] man.” Translations without that information are of no interest to me.

Bill, my question — not just for you, but more generally, of course — is why you feel you need to know that the original “really” says “son of [a] man” when you don’t feel that you need to know, for instance, what cases (dative, say, or genitive) the words are. I ask because I don’t think that most English speakers are equipped to evaluate the implications of grammatical details of the ancient Greek.

[…] That” blog. A good place to get started is with this one about the false dichotomy between accuracy and readability. This entry was posted in archaeology, prayer and tagged bible, joel hoffman, translation by […]

What if we asked a question suggested by sociolinguistics. Sociolinguists have noted that people use language not just to communicate, but to gain influence and power. So, what if we asked: “Are church people convinced to buy a more literal translation by their pastors who are thereby assured of a job explaining the more difficult to understand translations and/or have their prestige enhanced thereby?”

Ironically, my understanding is that some of the impetus behind the KJV — upon which so many “literal” translations are based — was to shift this interpretive power from the clergy to the people.

Linguistics is one of those subjects that is never taught in schools, and the average layperson is woefully ignorant in every respect. Most English-speakers in particular don’t know how other languages work or what is involved in good translation. I think they simply don’t fully comprehend the question. They think they are being offered a choice between accurate and less accurate translation, and naturally go for the former.

The Dunning-Kruger effect may also play a part. People want a literal translation because they think they are competent to accurately assess the actual meaning and intent of the passage given a word-for-word gloss. And the less people know about language, linguistics, and ancient texts, the more they are likely to overestimate their own competence. At the same time, the less they know, the more likely they are to doubt the genuine skills possessed by Bible translators in interpreting the text for the reader.

Paul,

Thanks for bringing this up. (For those who don’t know: The Dunning-Kruger effect reflects the notion that incompetent people are both unable to form a sound conclusion in the areas in which they are incompetent, and also unable to see the drawbacks of their unsound conclusion. The idea goes back at least to Darwin: “ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge: it is those who know little, and not those who know much, who so positively assert that this or that problem will never be solved by science.”)

My question here is not why average readers choose a literal translation. After all, they are being pushed in that direction by marketers, pastors, and even by the poll, which is decidedly lopsided. My question is why Bible-translation professionals — who ought to have the tools to make more informed decisions — nonetheless often ignore the recent exciting advances in translation and linguistics.

[…] they prefer accuracy over readability. Joel Hoffman from the blog God Didn’t Say That says this is a false choice and betrays a confusion on the part of lay people about how translation works. Joel says, […]

[…] Hoffman, over at “God didn’t say that,” cites David Roach in the Baptist Press, “most American Bible readers … value accuracy over readability.” Reading between the […]

I think that all of the problems arising from the “accuracy vs readability” issue arise, in part (or in whole) from the two terms — especially accuracy. Accuracy must be measured against an objective standard. In the case of biblical translation of the Greek or Hebrew, those languages no longer exist and the cultures the understood those languages have long since morphed away from the ones in which those phrases and words could be understood concretely. The best we can hope for is to be precise. But precision is unrelated to accuracy.

Accuracy (which I understand to mean the true meaning that the author(s) meant to convey) is largely an unachievable goal when tethered to the literal words. Personally, I prefer the word ‘understanding’. I think it captures the desirability of readability without the loss of that which the author(s) intended for us to comprehend. To convey the author’s meaning must be the first goal of the translator.

Whic raises the question of readability. A paper about quantum fluctuations might be clear, consise, coherent, and compelling (i.e., readable) to a theoretical physcist, but incomprehensible to the rest of us. It is noteworthy that some of the best know physicists are those who have written books about physics that make the subject understandable (there’s that word again) to the layman.

First get the meaning right. Then, express that meaning in terms the reader can understand. If the audience is composed of biblical scholars your translation will be different that if the audience is made up of teenagers participating in a Bible youth group.

Blessings,

Michael

>>>In other words, sticking to a word-for-word translation may be like opting for a literal biblical account of history and rejecting evolution, at least for some people.

Well, prefacing the Ten Commandments we find this testimony, “Then God spoke all these words, saying….” In fact, in relation to creation, twice in Exodus (ch 20 & 31) we find that Moses quoted God as having done creation in 6 days.

Also when Peter said, “no prophecy of Scripture is a matter of one’s own interpretation, for no prophecy was ever made by an act of human will, but men moved by the Holy Spirit spoke from God”, we see another way of how Scripture (or parts thereof) was delivered. Hence, the teaching here is that even “one’s own interpretation” played no part in it.

In light of what the Bible says about itself, I think that Bible readers cannot be blamed for wanting to know what the original words were (as a general rule), nor can they be blamed for thinking that this approach, for them, potentially distinguishes between ‘accuracy’ and ‘readability’.

[…] Joel Hoffman has a post up in which he suspects the survey is not about translation or language really.. Is the survey more about the SBC beef with gender accuracy in the TNIV and then the NIV 2011? […]

[…] Hoffman has a fascinating post which looks at an ambiguity that lies at the heart of much evangelical discussion about English […]

I am of the opinion that the writers of scripture employed a great deal of lateral thinking in their writing – ever alluding to what had been written before, even when the historical context is completely different and even while completely changing literary styles and genres. In the “son of man” situation, for example, “son of man” has associations with “son of Adam” and Psalm 2:

“What is man… and the son of man…”…

As well as “son of God” and “son of David”.

Translating as “human one”, while better English, damages those connections. Being a lateral thinker myself, that turns the text into very boring stuff! Instead of “human one” being one link in a long chain, it is suddenly an island.

Reading the “Book of Enoch” (actually a collection of scrolls), one wonders if the “son of man” was not originally an allusion to an exalted Enoch… at any rate, it is those scrolls that are the clear origin of the 1st century fascination with and expectation of a “son of man” figure, and that link should not be broken by divorcing the language.

I don’t see anything “inaccurate” or misleading about the phrase, “son of man” either. It is a bit formal, but conveys pretty well the idea of being an XY chromosome kind of Homo Sapien.

[…] with the accuracy versus readability, I think these poll results have more to do with culture than with translation, linguistics, or […]

I read a very accurate translation of the Bible. BUT, remember “The Way” Bible in the 70’s? That’s what got me started. Before the common written word, didn’t people just tell the story? If I were to talk to someone about Christ wouldn’t I just tell the person the story?

Perhaps, intent is more of a topic. While it’s true that “drift” can occur, it seems to me that if the translators have the intent of accuracy and keep going back to the original, that drift is minimized and it makes little difference just as long as the story gets told.

The debate will rage on for years. The truth is, “how can we wrap a finite mind around an infinite God”? Don’t most of us have it wrong somehow? Isn’t the object just to spread the Gospel? How many people are going to an eternal hell while we argue?