The King James Version (KJV): The Fool’s-Gold Standard of Bible Translation

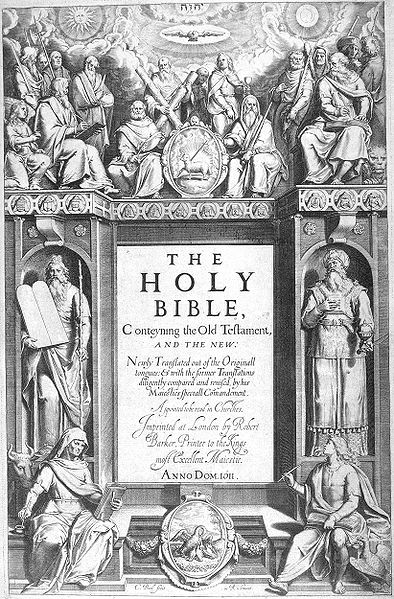

In 2008, as I was writing And God Said, I described the King James Version (KJV) as the “fool’s-gold standard” of English Bible translation. That was approximately 397 years after the watershed publication of the KJV, hardly a date worth noticing.

But today the KJV turns 400, and with that anniversary has come renewed world-wide attention to what certainly ranks as one of the most important and influential translations of the Bible ever. But some of the celebration is misplaced.

It’s not that I don’t like the KJV. I do. It’s often poetic in ways that modern translations are not. And I recognize all it has done both for English speakers who are serious about their faith and more widely. Dr. Alister McGrath is correct when he writes in his In The Beginning that the “King James Bible was a landmark in the history of the English language, and an inspiration to poets, dramatists, artists, and politicians.”

Equally, I appreciate the dedication and hard work that went into the KJV, as Dr. Leland Ryken passionately conveys in his Understanding English Bible Translation: “[f]or people who have multiple English Bibles on their shelves, it is important to be reminded that the vernacular Bible [the KJV] was begotten in blood.”

Yet for all its merits, the King James Version is monumentally inaccurate, masking the Bible’s original text. There are two reasons for the errors.

The first is that English has changed in 400 years, so even where the KJV used to be accurate, frequently now it no longer is. (My video-quiz about the English in the KJV — Do You Speak KJV? — illustrates this point.)

I no longer actively write this blog, but you can find me at Ancient Wisdom, Modern Lives

Subscribe Now I'd love to see you there!The second reason is that the KJV was written several hundred years before the advent of modern translation theory, linguistics, and, in general, science. Just as advances like carbon dating and satellite imagery help us know more about antiquity now than people did 400 years ago (even though they were a little closer to the original events), we also know more about ancient Hebrew and Greek now than they did 400 years ago. In fact, we know much more, both about the ancient languages and about how to convey them in translation.

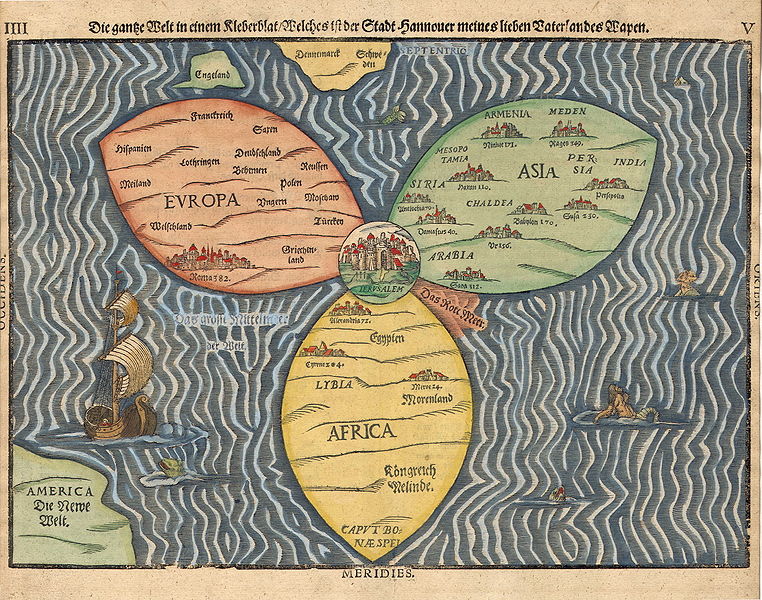

Like Heinrich Bunting’s famous 16th-century “clover-leaf map” of the world that adorns my office wall (the map puts the holy city of Jerusalem right in the middle, surrounded by three leaves: Europe, Asia, and Africa), the KJV translation is of enormous value historically, politically, sentimentally, and perhaps in other ways. But also like Bunting’s map, the KJV is, in the end, not very accurate.

And those who would navigate the Bible solely with this 400-year-old translation journey in perils.

Bible Bible translation Joel M. Hoffman King James Bible King James Version KJV translation

15 Responses

[…] The King James Translation (KJV): The Fool's-Gold Standard o… […]

I’m not so sure that one would ‘journey in perils’. My first bible was a KJV with no commentary or cross-references. I was about 13 at the time and had no Christian or church background. Looking back on it, I was more fraught with frustration than anything else. (That’s because I wasn’t well versed in old English and didn’t have an expository dictionary.) But when it comes to the various doctrines and points that people disagree on, I don’t believe it really matters a great deal what version one uses. I can potentially defend my ‘core’ beliefs with practically any version that’s not too paraphrased, because they all more or less say the same thing. This must the ultimate irony between the KJV and say, the NASB, which is now my preferred version.

I think the KJV is less accurate than most people realize.

One of the reasons it’s so hard to see the inaccuracies is that the other translations that are available are mostly based on the KJV: Some editions are specifically revisions of the KJV. Others, like the NLT or The Message, purport to be different, but they are actually based on it, too; they use different language, but frequently convey the same wrong ideas.

[…] better able to understand and convey the ancient languages of the Bible.On Dr. Hoffman's blog, God Didn't Say That, Hoffman compares the King James translation with the Heinrich Bunting’s famous 16th-century […]

I have to disagree. The fact that we have changed our meanings to English words does not mean that the translation of Gods word changes. We are not to conform His word to us, but we conform to His word.

So, Tonya, do you mean that the English language of the year 1611 was itself “God’s word” and we should conform with it?

English, like anything made by man, changes.

Books written in English a thousand years ago (600 years before the KJV) cannot be understood today — and could not be understood even in King James’ time — by anyone but a few scholars (that’s how fast our language changes).

Since the English of the year 1011 would have seemed a foreign language to churchgoers in 1611 (or 2011), we can expect that the English of 1611 will be just as incomprehensible for churchgoers in 2211 or 2611.

If any church is still KJV-only when that translation’s 800th or 1000th anniversary rolls around, either those churchgoers will be struggling with unintelligible Bibles, or they will be relying on their preachers to tell them what the KJV says, or they will have to have special KJVs that have the KJV text in one column and a translation of the KJV in the other column. Going to a KJV-only church in 2211 or 2611 will be like going to church in a foreign language — or like going to synagogue. (English 1000 years old might as well be Hebrew to us; so the English of 1611 will probably be as foreign as Hebrew to KJV-only congregations in 2611.)

I ask Tonya — and any other KJV supporters who read this — how much a language can change before Bibles translated into that language need to be re-translated. Is re-translation ever needed? Or has God promised somewhere that a translation made in 1611 will still be understood in the year 2611 … or the year 3611 or 5611 or 9611 if there are still KJV-only churches in that time?

Iacobi regis versio mihi maxime placet. Ego vero linguas antiquas ab nostris grammaticâ differre scio, ut vides, sed dictio anni MDCXI non valde nostrâ differt. Si hanc versionem intellegere nequimus, nonne opera Shakespeare in linguam hodiernam sunt vertenda? [A Latin response from someone who likes the KJV. -JMH]

Discipulus — there actually *are* translations of Shakespeare’s plays into present-day English: the “No-Fear Shakespeare” series prints the original on the left side, and a current translation on the right side, of each two-page spread. (I’ve seen even Shakespeare buffs — including teachers of English literature — pick up a “No-Fear” edition and say that now they knew, for he first time, the impact and meaning of many passages that they had only imagined they’d understood.

Your use of Latn for your message is pleasingly relevant to the question of when, and why, a text eventually needs re-translating. Imagine a Roman citizen of the early fifth century, resident in Gaul, who is miraculously transported to present-day Paris and is there given the task of telling his favorite joke to the next passer-by and having it clearly and correctly understood. Unless the passing modern Parisian had studied Latin, the Roman would fail in his mission. But imagine, now, that the Roman is allowed to stay home, and tells his favorite joke to his son — who in turn tells it to _his_ son, and so through two millennia. Each man in that chain of transmission understands the language of his father, and each believes it the same as his own speech: but each son speaks slightly unlike his father. The differences accumulate, even though each man in the chain (from Petrus in 411 through Pierre in 2011) might honestly swear that he spoke the tongue of his father and grandfather.

Now: imagine that the message to be passed through time is not a joke (passed mouth to ear, and gradually re-cast as the language slowly changes) but a fixed, written text of some greater importance to its readers and hearers.

You and I will agree that Pierre of 2011 wouldn’t understand the Latin Vulgate, or a Latin sermon, that Petrus of 411 might have heard read and would have well understood. Pierre would (at best) have half-understood a sermon in the French of 1211: and he only three-quarters-understands the French of 1611, as most of us only three-quarters understand the English of 1611. Pierre or you may decide — as you may decide — that three-quarters of understanding is good enough: but is it always? (Even with mere jokes, three-quarters of understanding can be as bad as not understanding a word.)

I submit that much of the KJV, like much of Shakespeare, sits just on the verge of intelligibility: as the clothes and shoes of a child may just barely fit, making it obvious that soon they’ll fit no longer. The right time to replace shoes and clothes is well before they become useless: why is this not also the right time to replace translations?

“Pierre or you may” should have been “Pierre may,” of course.

By the way: has anyone noticed that the most decided KJV-Only people usually believe that we are in the end times?

If KJV-Only belevers expect history to come very soon to an end,it is natural and logical that they’d expect the history of change in English to end very soon: in other words, while the KJV is still at least somewhat intelligible —

as you might not replace a child’s outgrown clothing, if you were certain that the child would die sometime this week.

Question to KJV-only believers:

Is it true that there are churches whose doctrinal statements /a/ require KJV-only, and and /b/ state that all doctrine of that church is in the Bible?

If that is so, then where in the Bible do they get their doctrine of requiring KJV-only?

Hm, I did not realize that Shakespeare had been translated. I enjoy and understand the works in their original state, but perhaps that’s not for everyone.

I would respond to all of your points, but time is lacking. Let’s simplify my response to say that I agree with your points on Latin and old French, but that I don’t believe that the KJV has reached, or is soon to reach, the point at which it will need to be retranslated.

I will not live to see whether this is the case or not, but I think that such things as the Internet, educational television, widespread education and so on will greatly slow the evolution of our language, meaning that things that are understood now will be understood for centuries to come.

Down the the questions in your last post:

No, I have not seen a church that holds both /a/ and /b/. They usually hold that there are things that are not in the Bible, but are required nonetheless, such as abstaining from gambling, tobacco, etc.

Just a note: I don’t check this page regularly, so I probably won’t see comments directed to me personally.

[…] less in what it tells us about the original text of the Bible — I did, after all, call it a fool’s gold standard — and more in its historical and cultural role. (For more on why I think the KJV is now […]

Re:

“I think that such things as the Internet, educational television, widespread education and so on will greatly slow the evolution of our language,” —

Others, however, are finding that language changes more rapidly, not less, at present: despite all the things you mention, the English of Singapore and the English of Australia (for instance) are measurably less like each other now than tHey were in 1950.

–I accept that we have seen a lot of advances in linguistics in recent decades. This may be particularly true for the languages of the Bible.

–If the goal is to do an ever better job of polishing the literal meaning of the Bible’s metaphors and allegories, then I suppose today’s Bible scholars are making incredible progress. But, if the goal is to make sure the wisdom beneath the literal meaning, is allegorized as well for us as it was for its original readers, I think we are continuing a downhill slide that has been going on for nearly two millennia.

–Our religions that use the Bible, only teach about ordinary earthly morality as far as I can tell. They are more like a political party, or branch of the government, or a guardian of culture, than a source of spiritual wisdom.

–Religions should show us excellent examples of human behavior, but clearly that is not the case. Do you feel at all safer when you are shopping for a home or a used car and you learn that the seller attends religions services? I don’t, in fact I take extra precautions, because they may well believe that God wants them to really come out ahead in the transaction.

–If today’s supposedly better translations are making ordinary earthly morality more teachable I can’t see any evidence of it. If those better translations are helping more people to grasp the spiritual wisdom of the Bible, where are these people? I occasionally do web searches looking for any religious sites showing any evidence of actual spiritual understanding. Any spiritual understanding that I am able to recognize, is never on a site dedicated to Judeo-Christian writing. Some sites mention Bible passages that teach the same concept as one in the Bhagavad Gita or a Buddhist sutra or some Taoist writing, but apparently no one interested in only Judeo-Christian writing, is obtaining spiritual understanding. Or if they are, they are keeping quiet about it.

–As I grow in spiritual understanding, studying the writings of many different spiritual traditions, it seems I learn new concepts somewhat gradually. Sometimes they really click into place for me when I recognize them in one of the stories or sayings in my KJV Bible.

–I hope that scholars do create a better English translation of the Bible than the KJV, but I doubt that they have done so yet.

[…] The background is that I told Travis that I believe that The Voice is flawed, and I’ve told her in the past that I also believe that the KJV is flawed. (“The King James Version [KJV]: The Fool’s-Gold Standard of Bible Translation.”) […]